Illegal Market on Pierre Jeanneret Objects: Reeditions, Hommages, Fakes

2025 | 11 | 20

Pierre Jeanneret’s furniture from the Chandigarh project has become one of the most sought-after design collectibles in the world. This success has created a massive illegal market operating on multiple levels, each with its own logic and methods. Some manufacturers ignore copyright entirely. Others exploit legal ambiguities and hypocrisy. And then there are the outright counterfeiters producing fakes. These are aspects to know before deciding which direction fits to you. Especially since all suppliers claim to offer originals. 1. Illegal Reeditions?

Suppliers like Srelle (Belgium), Phantom Hands (Ireland), Dimo (Ireland), Klarel (USA), and Objet Embassy (Holland) and many others are flooding the market with Chandigarh furniture, claiming to honour Pierre Jeanneret’s legacy. But here’s what they don’t tell you: Jeanneret’s copyrights are protected until 2037, and none of these sellers have licences. Their defence? The Chandigarh workshop was a collective effort where everyone owned everything together, they create a story of a “open source design approach”. It sounds democratic, almost noble. Except it’s completely wrong. The copyrights belong to the actual authors – Pierre Jeanneret or Le Corbusier. Not automatically to project managers or architects working under their direction, for example Balkrishna Doshi. Take Eillie Chowdhary and the Library chair – since it’s probably her design, the copyright goes to her. If she was executing Jeanneret’s design, it would go to him. But all these suppliers operate as if this question doesn’t matter, as if they can bypass it entirely by claiming some shared, collective ownership. They work without permission, hiding behind a romantic story: that these pieces existed in some copyright-free limbo because intellectual property didn’t matter back then, or because they’re using “original techniques.” It’s a convenient fiction. Indian and Western copyright law exists precisely to protect the author’s rights and prevent this. The chairs weren’t abandoned. They weren’t forgotten. Jeanneret’s estate owner simply isn’t protecting the rights. So nobody cares. And the illegal distribution continues worldwide – from Belgium to Ireland to the USA to Holland – unchecked. 2. Cassina names copies simply hommages

Cassina owns the Corbusier copyrights. They’ve spent decades advertising their “originals.” They’ve built an empire on authenticity. So when they couldn’t get the rights to Pierre Jeanneret’s Chandigarh furniture, they did something remarkable: they simply copied it anyway and called it “hommage.” It’s a highly problematic. They talk about tribute, about honouring Jeanneret’s legacy, carefully avoiding mentioning that it’s by Pierre Jeanneret. But compare their homages to the originals – same sizes, same proportions, same details. No essential differences. These aren’t interpretations. They’re reproductions. The same company that aggressively hunts down suppliers violating Le Corbusier’s copyrights now pretends the rules don’t apply when it’s profitable. They’ve found a lucrative loophole: if you can’t get the rights, just rebrand appropriation as respect. 3. Fraud: New chairs sold as Vintage Originals

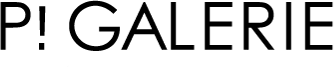

While one market focuses on new items, there is another market of galleries and vintage sellers which offer old, authentic items by Pierre Jeanneret. Since they are valuable items, there are frauds, which try to offer brand-new furniture artificially aged and sold as 1950s–1960s originals, less as copyright infringement, but as criminal fraud. The market is quite innovative. Selling new objects as vintage is a criminal offence and punishable by prison in the EU/US under fraud statutes. But there are more subtle frauds, where damaged parts have been replaced but not appropriately documented. Acting like each part is original mid-century, and avoid that part. Galleries or vintage sellers act here as not knowing or pretending, but not knowing would not protect them against the accusation of fraud. All this is not unethical; it’s criminal. 4. Vintage Originals

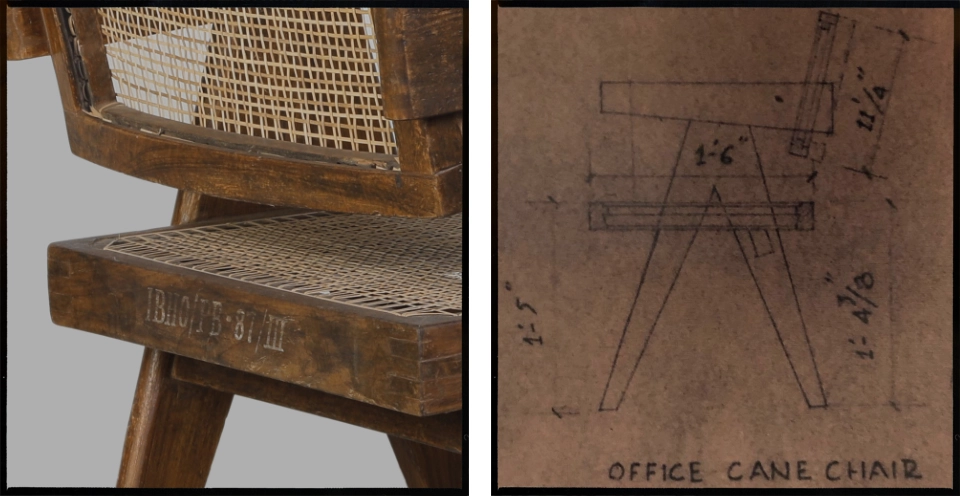

Vintage chairs from the Chandigarh period are the most authentic option available. Unlike reeditions or copies, they are genuine historical objects with inherent value. While reproductions lose value immediately after purchase, vintage pieces maintain or increase their worth over time. Each vintage item from Chandigarh is unique. No two chairs look exactly alike, and this individuality gives them an aura that mass-produced items simply can’t replicate. Most reeditions appear sterile – perfect shapes, flawless wood surfaces. Vintage pieces have patina, traces of use, and subtle distortions that tell their history. If you prioritize technical perfection, these authentic items with their imperfections won’t suit you. Price is another consideration. A vintage floating office cane chair (link to our PJ-SI-28-A) costs two to three times more than a reedition. For large-scale projects like hotels, the lower price of reproductions seems practical – but this ignores the fact that vintage pieces appreciate while copies depreciate. However, even the vintage market has risks. You might pay premium prices for a fake or a heavily restored piece with replaced elements. Success requires either expertise to authenticate pieces yourself or finding a gallery with a proven reputation. How to Decide?

Choosing isn’t just about comparing options. There are deeper questions worth considering. The ethical question:

Is it important to protect the rights of the author? Since Pierre Jeanneret is dead, copyright protection benefits the rights holder, not the creator himself. Ignoring copyrights isn’t ethical, but the harm caused may appear negligible – it’s often treated as a gentleman’s delict, and a bit of Robin Hood mentality can make it easier to justify. Every supplier comes with a moral story: protecting the heritage, respecting Chandigarh’s vision, honouring original techniques, supporting gifted carpenters. These marketing strategies cleverly sidestep the copyright issue. But the question remains: is copyright always something good we should respect, or is it a blocker creating a monopoly that prevents humble design from being appreciated by people with smaller budgets? That depends very much on your perspective. The quality question:

Precision of shape doesn’t define quality here. It’s about the proportions, how closely they follow the original vision of the author, and the beauty of the result. Colour of wood, richness of texture, and thickness of the beams define the character of each piece. The patina is the most relevant aspect – it makes these simple geometric shapes come alive and defines the uniqueness of each piece. This touches on what philosopher Walter Benjamin described as the “aura” of artworks when questioning the reproductions of art. The uniqueness and history of an authentic object make us see more in it, project more meaning into it, creating a different relationship than we have with what we recognise as a reedition or mass product. Aura and patina are the elements that make vintage items richer – and these are nearly impossible to replicate in reeditions. The price question:

The price question: Some see these chairs as investments, some as collectibles, some care purely about authenticity. But if budget is your priority, then a reedition becomes a legitimate option – a way to afford an object you love without financial ruin. In the end, it’s all about priorities. What matters most to you: legal clarity, investment value, aesthetic soul, or simple affordability? There’s no universal right answer. Just understand what you’re buying, what you’re supporting, and what trade-offs you’re making. Back